From sacred parasols to storm-ready canopies, this is the global history of umbrellas.

In this in-depth history, we trace the object’s earliest precursors, the inventions and materials that shaped its evolution, and the cultural meanings it picked up along the way. Across centuries, small design decisions changed how we eat, travel, dress, and shop—one humble tool at a time.

Sacred Shade: Parasols in Antiquity

Long before umbrellas were tools against rain, parasols symbolized rank and ritual. In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, attendants shaded rulers with canopies mounted on poles, a moving sign of authority. In India and Southeast Asia, parasols also had religious significance; in Buddhism, the **chatra** represented spiritual protection. Classical Greece and Rome knew the parasol as a fashionable accessory, often associated with women and processions. These early canopies were crafted from organic materials—leaves, paper, silk—stretched on frames of wood or bone. They blocked sun, not showers; water would have damaged the coverings and swelled the ribs.

From Parasol to Umbrella: Waterproofing and Materials

The transition from sunshade to rain shield depended on materials. In China and Japan, oiled paper (such as the Japanese **wagasa**) made canopies water‑resistant. Lacquered bamboo frames kept them light yet sturdy. As the idea spread west, innovators experimented with waxed fabrics and tightly woven silks. In early modern Europe, umbrellas were uncommon and sometimes mocked; a gentleman braving rain with a canopy could draw jeers. But practicality won. By the 18th century, London’s downpours and muddy streets made umbrellas desirable, and makers refined designs with better coatings and stronger ribs.

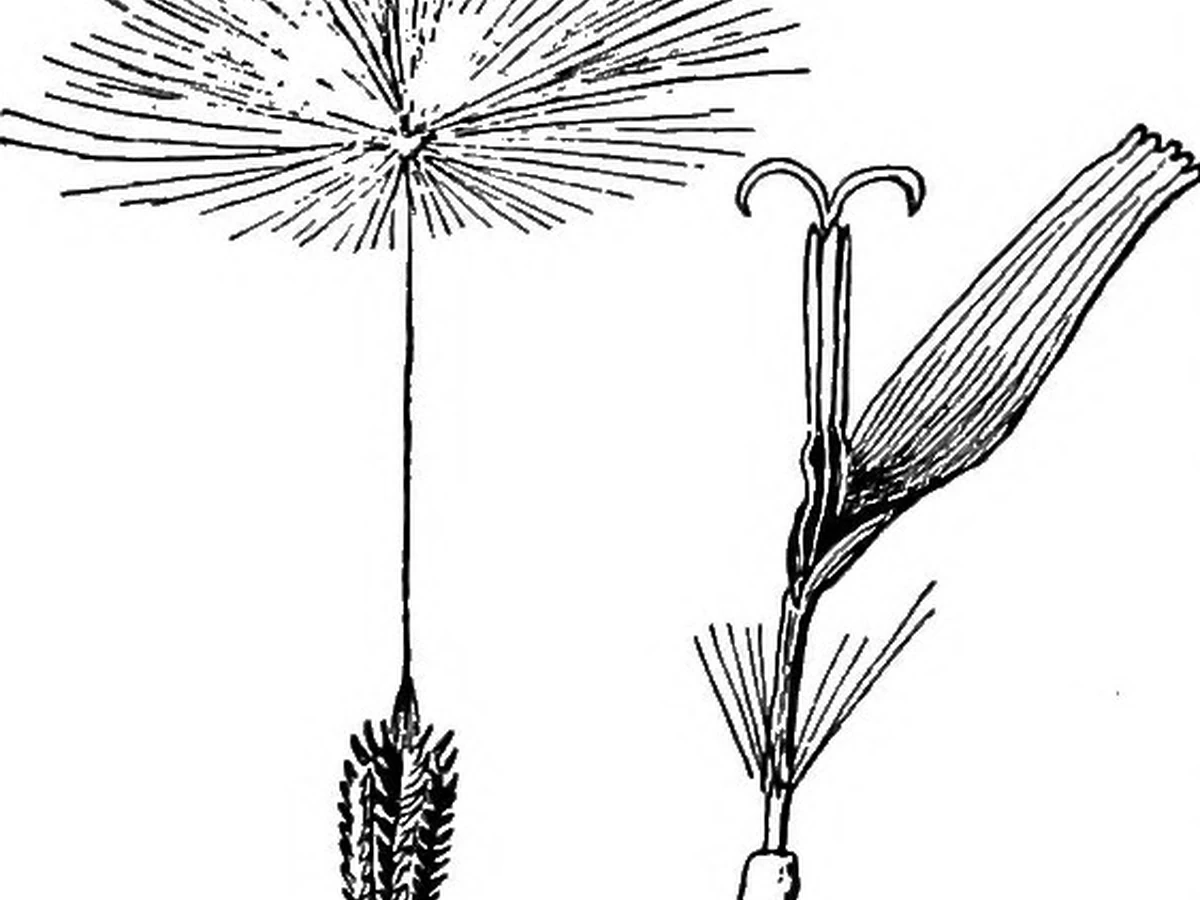

Mechanisms and the Birth of the Folding Frame

The defining leap was mechanical: collapsible frames. Steel ribs and stretchers, along with notched sliders and springs, allowed umbrellas to open smoothly and fold compactly. The 19th century saw patents for improved joints, tips, and ferrules; by the early 20th century, pocketable models made carrying an umbrella as routine as a hat. Synthetic fabrics (nylon, later polyester) replaced silk, resisting water and abrasion. Today, carbon‑fiber ribs, vented canopies that release gusts, and auto‑open/close buttons reflect a century of engineering focused on comfort in a storm.

Fashion, Identity, and Cultural Imagery

Umbrellas also became powerful images: black canopies in film noir streets; brightly colored parasols at seaside resorts; paper umbrellas in festive drinks. In many cultures, parasols remain ceremonial—the Burmese **hti** crowning pagodas, or ornate umbrellas shading deities in Hindu and Buddhist festivals. Designers collaborate with fashion houses on prints and sculptural handles; artists use umbrellas in installations symbolizing shelter, migration, or the weather’s caprice. The umbrella’s dual identity—as tool and icon—keeps it relevant in both wardrobes and museums.

Repair, Sustainability, and the Future

Cheap umbrellas break easily, creating a quiet waste stream after every storm. A counter‑movement encourages repairable frames, replaceable canopies, and modular parts. High‑end makers tout metal fittings and serviceable joints; urban libraries lend umbrellas to commuters. Some manufacturers use recycled plastics and bio‑coatings, aiming to reduce environmental impact. As cities face more erratic rain and sun, the umbrella continues to evolve—straddling fashion and function, ritual and resilience.

Curiosities and Fast Facts

- Materials and mechanisms reveal broader industrial trends—when one improved, the other followed.

- Small objects often carry big etiquette rules; what’s polite in one era or region can be taboo in another.

- Mass production standardized dimensions but also inspired niche, artisanal revivals.

- Design changes frequently track public health, safety, and accessibility standards.

Conclusion

The History of the Umbrella is more than a footnote of design history. It’s a case study in how simple tools absorb innovation, shape everyday rituals, and reflect the values of their time. From raw materials to refined mechanisms, the object’s journey shows how a little ingenuity goes a very long way.

Next time you encounter one, consider the craftsmanship and cultural layers packed into such a small thing.